A Q&A with Bad Indians author Deborah A. Miranda

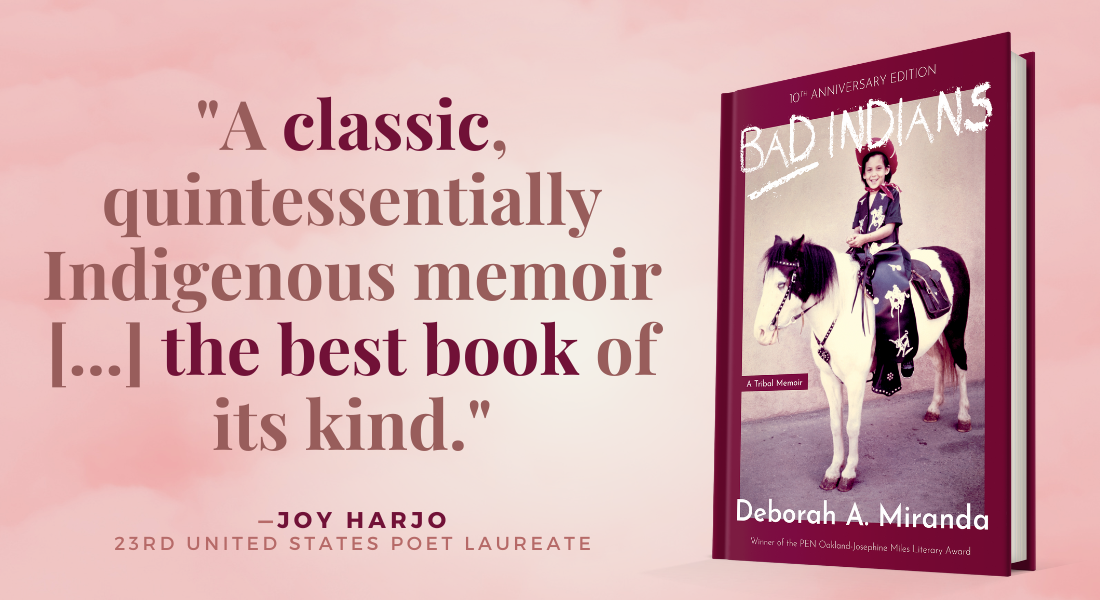

The critically acclaimed mixed-genre chronicle of Native American survivance by poet-professor Deborah A. Miranda debuts in hardcover with over 60 pages of new material in honor of the book’s 10th anniversary this Indigenous Peoples Day. The best-selling first edition of Miranda’s revolutionary memoir—adopted widely by book clubs and classrooms across the nation—is a classic of Native American Literature and an indispensable entry point for anyone seeking a more just telling of US history.

Featuring never-before published essays and poetry, the 10th Anniversary Edition of Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir plumbs deeply into Indigenous displacement, genocide, resilience, and solidarity in a poetically rendered corrective to prevailing narratives of Native erasure. With dauntless emotional honesty, Miranda challenges the pedagogy of California Missions history, envisions Native life through colonization, and reflects movingly on intergenerational legacies of colonial trauma and collective liberation.

It’s been a decade since Bad Indians was first published. What gives the lessons of this book continued, or even deepened, urgency?

Bad Indians is a response to the erasure and silencing of California Indian experiences and history by colonial powers and cultural mythology—history books, tourism, the Catholic Church, the United States government, and educational institutions. Even as California Indian voices become stronger, challenges to Indigenous rights and tribal sovereignty keep coming. In the 2015 canonization of Junipero Serra, and in the absence of an accurate California history curriculum, we still see attempts to erase historical crimes—attempts often made by descendants of the very people and institutions that committed those crimes. In 2017, the California State Board of Education published a history and social science framework that did not mention Congress’s funding of bounties for Indian deaths, or California governor Peter Burnett’s open insistence on waging “a war of extermination” against California Indians. Obviously, we still have much work to do.

Many educators now teach your book in universities and even high schools. How have you’ve seen this book affect students?

One undergraduate told me, “I’m 20 years old, born and raised in California, and I’ve never heard any of this history about the Indigenous people in my own state. I never realized that my education has such huge holes in it!” I hear this story a lot; students feel the book is a wake-up call to ask more questions, demand better answers. One young Indigenous woman walked up to me after a reading at a university, handed me a folded note, said, “Thank you,” and walked away. The note began, “It happened to me way before fourth grade.” She went on to write about how reading pieces in this book peeled away layers of shame and gave her a new perspective about connections between colonization and contemporary sexual assault of Indian girls and women.

What hopes do you have for this book over the next ten years, and beyond?

I hope Bad Indians keeps motivating readers to educate themselves about the long-reaching effects of colonization in everyone’s lives, and to act on that knowledge—whether that means supporting California Indian communities, cultures, and arts, or finding ways to heal themselves and their communities. I also hope the book encourages other young Indian people to see that yes, Indians can write poetry, fiction, essays, scholarship; that our own stories have value and meaning, that we can use language and art to mend the wounds caused by colonization that often keep us isolated from one another. This is what we need in order to form the community that nourishes our future.